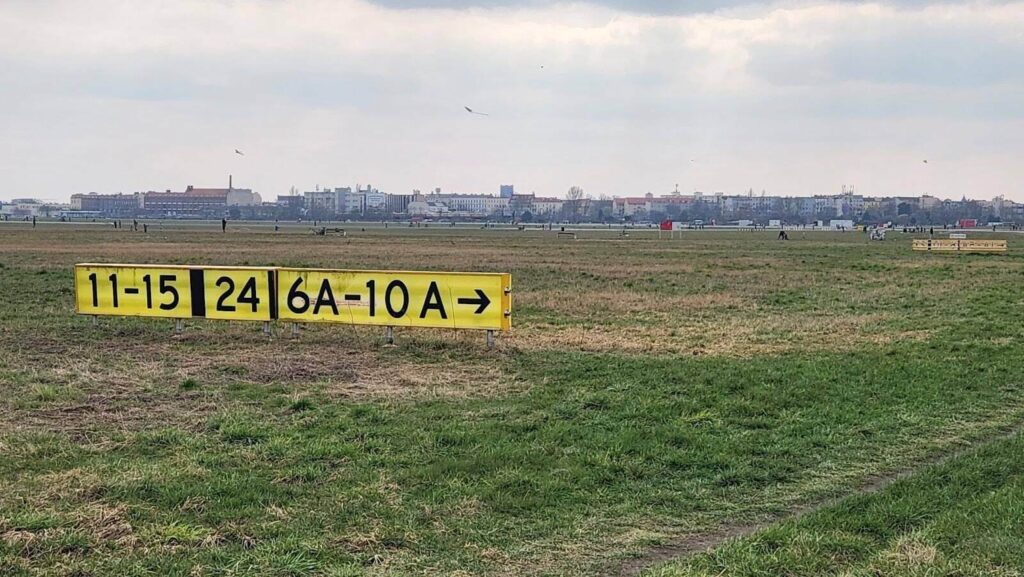

The wind blows across the wide, empty fields and runways of the former Berlin-Tempelhof Airport. Kites and windsurfers dot the sky, and people gather with friends and family to bask in the early spring day. Yet, this same breeze also passes through the converted shipping containers and disused hangars where hundreds of refugees live.

This juxtaposition tells the unseen (at least internationally) story of Berlin and Germany. According to recent statistics compiled by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), around 2.5 million persons are currently living in Germany as refugees and asylum seekers, more than any other EU country and only trailing Iran and Türkiye globally—in a nation of only 84.7 million inhabitants, around a quarter of the United States’ total population.

Because of these factors, Germany is one of the most apt places in the world to study the current dynamics of migration, both in the European Union and globally. Its capital Berlin is at the center of this conversation, as both a major host city and the seat of government power. During spring break 2024, William Donahue, the Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Professor of the Humanities and director of the Initiative for Global Europe at the Keough School of Global Affairs, organized a trip to Berlin with students from the course Europe Confronts the Refugee Challenge to study migration in Germany firsthand. The course and trip were supported by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies as part of its curriculum.

While the course offered the chance for students to engage with migration in the classroom and speak with the world’s leading experts in migration, it went one step further. Students went to Berlin to, as Donahue put it, “compare theory and research with practice, with the way in which this work with refugees and migrants is actually conducted by policymakers, think tanks, grassroots organizations, church organizations, etc.”

Some of these organizations engage with migration directly—such as the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI), the state office in Berlin tasked with registering asylum seekers (LAF), the International Rescue Committee (IRC), and many others—while other groups take a more observational role in Germany, such as the U.S. State Department through the American embassy in Berlin.

Ethan Chiang, a first-year student studying global affairs, noted how this experience offered a unique opportunity to see the “convergences and divergences between the fields of academia, policy, and civil society and how they interact with each other to welcome and integrate refugees and migrants into German society.”

Several of these “convergences and divergences” emerged throughout the week as points of tension and sources of questions. They served as guiding threads between the perspectives of the distinct (and sometimes opposing) stakeholders who spoke with the group.

The German asylum process

When asylum seekers register in Germany, they generally do so in Berlin and other major cities; however, once their application is approved, they are assigned to one of the 16 federal states and served within that area. The welcome center in Berlin will usually provide rail tickets to asylum seekers after their claim is processed to get them to their assigned location. Each state then provides for the immediate needs of the asylum seekers in its jurisdiction.

While this process helps alleviate the uneven impact of migration—a common problem experienced in the United States and elsewhere—in practice it is complicated. Many people want to live in Berlin, for example, because of existing diasporic communities or family members who live there. However, Berlin, like much of the United States, is currently facing a housing shortage. The state office team on the ground described each day as a struggle to get just one more apartment for another family.

With increased migration due to conflict around the globe, the refugee response system is over capacity. At maximum, it can only process around 300,000 applications each year; today, Germany struggles to meet the demand and place each person, leading to frequent delays. One lifeline that has kept this system from being completely overwhelmed has been the EU implementation of Temporary Protective Directive (TPD) status for Ukrainians seeking refuge. This status allows them to bypass the application process (at least temporarily). As a result, around one million potential applicants (more than three years’ capacity) have avoided entering this saturated queue.

Tensions in the national labor market

By most accounts, including the DIHK Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Germany faces worker shortages across industries. In November 2023, an estimated 1.8 million jobs were not filled. To maintain its productivity and industrial competitiveness, Germany needs many more workers. Immigration is a natural solution.

However, many obstacles to full labor participation endure. One factor multiple organizations and speakers mentioned was the language barrier. While this trend is shifting slowly, in most sectors of the economy, the German language is required to function in a professional role. Furthermore, most professions in Germany require specific certifications that might not have an equivalent in other nations.

These hurdles to entering the labor market can also force migrants to undergo a process that Philipp Heiermann from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) referred to as “de-certification,” which is when a migrant worker takes a role that has fewer professional requirements than what they hold in their home country. De-certification seems to be particularly prevalent among the 1.1 million (as of February 2024) Ukrainians seeking refuge in Germany today, as they are often highly educated and hold terminal degrees in Ukraine. Still, many cannot work in equivalent positions in Germany, and if they can, a lack of childcare capacity can also create an additional barrier.

This tension between the need for workers and the barriers preventing incoming migrants from filling the roles the economy needs most is one of the central issues that Germany faces today.

A further tension arises when considering a question posed by Timo Tonassi, assistant research professor at Georgetown University and an organizer of the trip itinerary, during his first debrief session in Berlin: “What does someone’s need for protection have to do with your economy?” Whether there is a need for workers or not, people who apply for asylum still need help, but it is often too easy to conflate these issues when addressing them at a policy level.

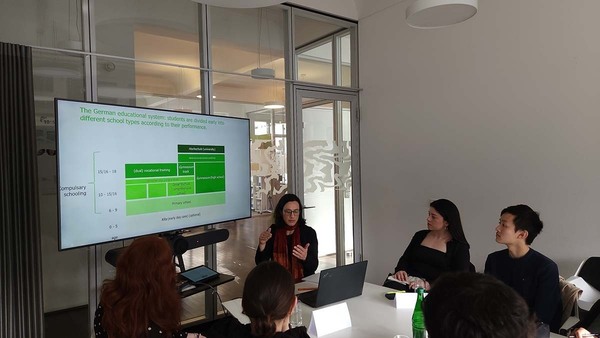

Education: How to serve the needs of a multi-lingual, multi-cultural student body

The German educational system includes excellent public schools, highly-trained teachers, and high government investment. 351.3 billion euros were invested into public education in 2021, which represents 9.8% of Germany’s total GDP. Clearly, education is a major national priority, and as such, it is compulsory for children in Germany—even children seeking asylum.

While this inclusion into the education system empowers children from migration backgrounds,* there can be significant challenges to meeting their needs in practice. Like many essential workers in Germany, teachers are in short supply, meaning that these educational professionals are stretched beyond capacity. Compounding this challenge are concerns about the short supply of teacher training resources to improve cultural sensitivity, enhance language-teaching tactics for non-native speakers, and prevent negative stereotypes about migrant students from becoming self-fulfilling prophecies, either due to teachers believing them or failing to counter them. Notre Dame students met with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Berlin, which offers this kind of course, and they reported an extremely high demand for their curriculum.

Students also visited Canisis-Kolleg, a private school established and run by the Ignatian Order in Berlin. This school has a specific program that offers migrant students the resources they need to succeed while allowing them to continue to interact with and form relationships with native German students in the same building. Beyond additional classes and courses designed for students learning German as a second (or third, fourth, etc.) language, this specialized program connects these students with networks and mentorship opportunities to help them discern their career paths. The Notre Dame group met with students from this program, who spoke more than 15 languages altogether. Students from Notre Dame and Canisis-Kolleg alike had the chance to ask and answer questions. Not only did the conversation focus on education in Germany but it also included the sharing of perspectives on U.S. education and culture.

In many ways, the model of Canisis-Kolleg is a success story, but as with many other challenges, the difficulty in German education is not in quality but in scale. The main question: How will the system meet the nation’s educational needs while working with a shortage of teachers?

The specificity of the moment

What was truly unique about this trip to Berlin was that migration was a major focus of public attention at that specific moment. Current events in Germany prompted anti-far-right protests, including one across the city from where the group met on March 15. These demonstrations were, according to reporting, opposed to anti-immigration and anti-refugee rhetoric. Despite the rise in popularity of these views, clearly many Germans still want their nation to be welcoming.

Meanwhile, strikes at Lufthansa, Germany’s largest airline, and the state-owned Deutsche Bahn railway service, represented a visible sign of the growing strain on the labor market. Luckily, the course group was minimally affected by these strikes, but travel disruptions occurred across Germany while they were in Berlin.

Migration. Labor (including workers’ rights). Policies and politics.

Amid the urban beauty, incredible public transit, and historic sites found in Berlin, the same early spring wind touches the faces of Berliners and asylum seekers alike. At this moment, Notre Dame students had the chance to ask hard questions and provide input to leaders, stakeholders, and advocates. In so doing, they engaged with one of the core research priorities of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies: “peripheries.”

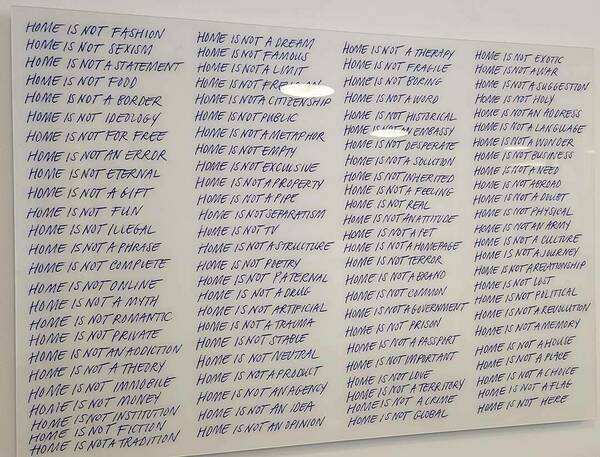

Migrants and refugees are often seen as outsiders, but their perspectives are essential to our understanding of the people they seek to call neighbors—perhaps those they wish to fly kites alongside. They join together, native and migrant alike, to shape the places they seek to call home, temporarily or otherwise. To understand Germany as it is, to understand Europe as it is, we must grasp this foundational dynamic.

Otherwise, we risk studying a caricature, an imagined sense of “European” identity, instead of the true stories, with all their tensions, of real people. Migrants and refugees are Europe. Only with this realistic view can we start to ask the questions “So what now?” and “How do we act?”

After all, we cannot lose sight of the shelters for the kites.

*In Germany, “migration background” is a specific term employed in education to indicate that a student was born in another country or at least one of their parents was. Several speakers the Notre Dame group met with used and defined this term.