The end is near …. Will we avert it or create it?

I have been playing a lot of Stellaris lately with the recent Apocalypse DLC. This expansion adds, among many changes and updates, the new Colossus-class spacecraft: Stellaris’s version of the Death Star. These enormous, station-size ships can be equipped with a surprisingly diverse set of world-ending weaponry. Is destroying the planet directly too crass for you? Try encasing the planet in an impenetrable shield so that they are forever cut off from contact with the rest of the galaxy, or perhaps you would prefer to beam spiritual truth into a population’s minds, prompting them to accept your religion.

These varied and sometimes fanciful notions of what the “end of the world” can be prompted me to reflect on other depictions of the apocalypse in games and what they might mean. Helpfully, the recent release of Chrono Trigger on Steam brought this beloved classic to my attention; and any discussion of Chrono Trigger cannot be complete without comparing it to its contemporary Final Fantasy VI. The debate over which of these titles is superior is unsettled, but the consensus clearly holds them both as masterworks of the RPG genre. And both center their stories on the concept of the end of the world.

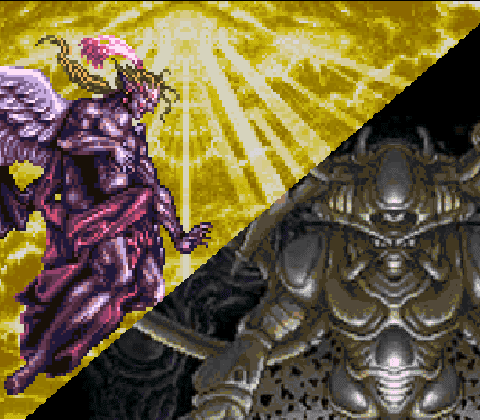

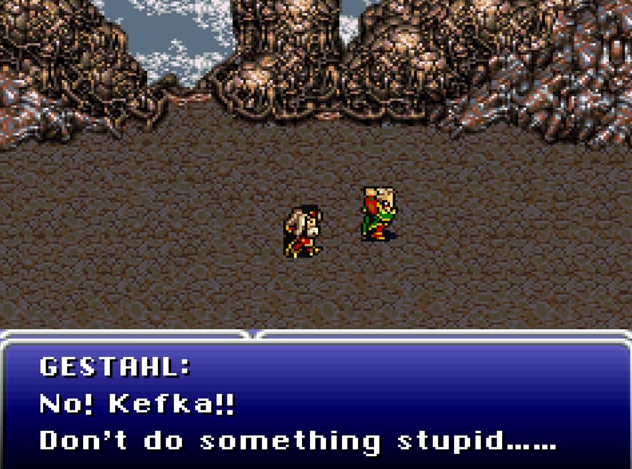

Curiously, both apocalypses are not quite “the end” for humanity. Survivors come together and rebuild, although in vastly different situations. Although the initial impact of Kefka’s rearranging of the continents has a high death toll, much of Final Fantasy VI’s world is surprisingly intact. Most of the cities the party visited before can be found again largely unchanged beyond a few damaged buildings and a browner color palette. Kefka’s long-term damage seems to have been done to the climate and the culture. The whole world is now very dry and desolate with much less vibrant colors and wildlife. Although the topic is not directly addressed, we can assume that this climate change has severely impacted the world’s agriculture, meaning that feeding the population must be an incredible challenge. From a cultural standpoint, Kefka’s ascension has effectively destroyed national identity. The fight between the Empire and Returners is inconclusively and immediately halted. Instead of these conflicts, the individual towns are now simply trying to avoid angering Kefka and drawing his “Light of Judgment,” a kind of deathray, to their community. There is even a Kefka-obsessed cult living in a tower, endlessly chanting and pacing to appease the world’s new overlord.

And therein lies the real difference between these games’ apocalypses: at the end of Chrono Trigger the apocalypse doesn’t happen, while Final Fantasy VI’s world is irrevocably altered even after Kefka is defeated. At face value, this distinction arises simply because time travel exists in the former and not in the latter narrative, but what causes the world to end also plays an important role.

Lavos is an impersonal entity. It acts more as a natural disaster than as a true antagonist. It arrives in the prehistoric era from space, completely beyond the control of primitive human beings or even the more advanced reptites. It’s growth toward the Day of Lavos in 1999 appears inevitable, as several attempts throughout the centuries to weaken it fail.

Kefka could not be a more perfect foil to Lavos, as his actions are portrayed as highly personal. His madness and hate was released by, if not created by, his failed Magitek infusion. His rise is the result of unchecked human ambition.

For example, an asteroid might be redirected through our knowledge of astrophysics and spaceflight engineering. However, this same human power can be the cause of irreversible damage to the world and our society.

These two RPGs released by the same company in the mid-90s hold these two truths in tension, and even two decades later, we still do not know which path human advancement will take. This enduring question might be one reason both Final Fantasy VI and Chrono Trigger are still so well-loved today and, even more so, why they are so often remembered together as a set. Seeing both visions of the future reminds us to approach innovation with caution even as it fills us with hope, lest we inadvertently trigger an irreversible apocalypse in our attempts to prevent one.